The Persians were coming. In the summer of 480 B.C.E, the Greeks’ plan to halt King Xerxes’ army on land and at sea had failed. Following the loss of the narrow pass at Thermopylae and the later retreat of the navy from Artemisium, the Greek mainland lay exposed. Fear set in across the peninsula, but the Persians’ main target was Athens. Having found out that their Spartan allies would not be coming to help, the Athenians, under the influence of their prominent statesman Themistocles, took drastic action. They decided to evacuate.

‘…the Athenians returned to their own harbours, and at once issued a proclamation that everyone in the city and countryside should get his children and all the members of his household to safety as best he could. Most of them were sent to Troezen, but some to Aegina and some to Salamis. The removal of their families was pressed on with all possible speed…’

Herodotus, The Histories - 8.41

According to Herodotus, our best written source for the Persian Wars, the decision to vacate the city was sudden, and the exodus from Athens was a hurried, chaotic affair. Having been forced to concede the fight on land and leave their home to be sacked and burned by the enemy, the Athenians now only had one option left: to goad the Persian fleet into a battle at sea. The stage was set for the Battle of Salamis...

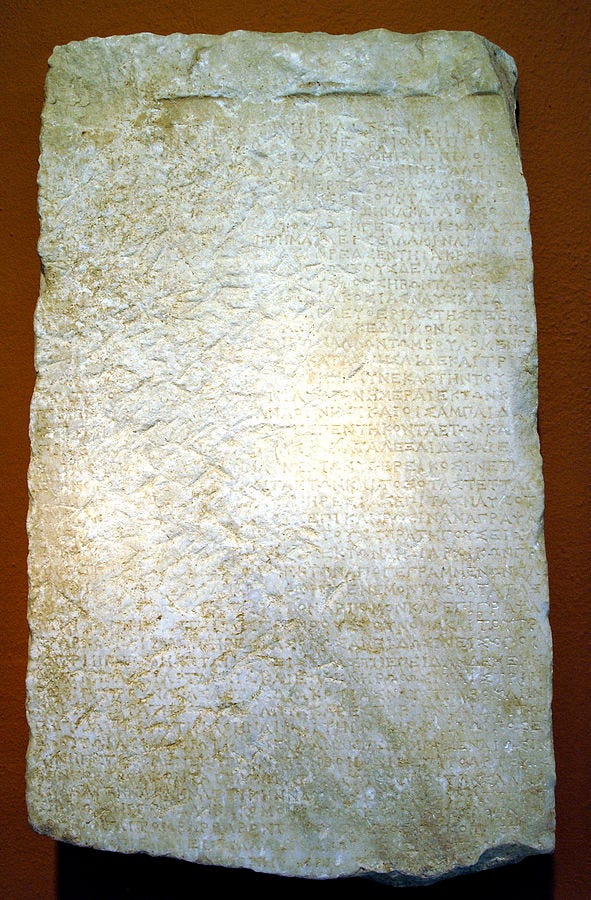

Over two thousand years later, in the modern Greek village of Troezen, a farmer found something. It was a bashed-up, inscribed marble stele, around 60cm tall and 40cm wide. He thought it would make a good doorstop, and kept hold of it until 1959, until a schoolteacher managed to convince him to part with it (and just buy an actual doorstop). It was then displayed locally, as part of a small collection of ancient artefacts from Troezen. The following year, it was found and translated by American classicist Micheal H. Jameson. What he found was astonishing. The inscribed text seemed to be a surviving copy of the very decree ordering the evacuation of Athens.

‘Resolved by the Council and the People on the motion of Themistokles, son of Neokles, of the deme Phrearrhoi: to entrust the city to Athena the Mistress of Athens and all the other gods to guard and defend from the Barbarian for the sake of the land. The Athenians themselves and the foreigners who live in Athens are to remove their women and children to Troizen ...the archegetes of the land. ...The old men and the movable possessions are to be removed to Salamis.’

E.M. 13330, Trans: Jameson, 1960

The Themistocles Decree (also known as the Troezen Decree), National Archaeological Museum of Athens E.M. 13330

It became commonly known as the Themistocles Decree, and this alone would have been a rare and remarkable find. Surviving decrees from antiquity were uncommon, especially ones outlining events as important as this. But that wasn’t all. Further on in the inscription, it becomes clear that this version contradicts the previously accepted version written by Herodotus.

‘When the manning of the ships has been completed, with one hundred of them they are to meet the enemy at Artemision in Euboia, and with the other hundred of them they are to lie off Salamis and the rest of Attika and keep guard over the land.’

E.M. 13330, Trans: Jameson, 1960

This passage claims that the Athenians evacuated the city before the battles at Thermopylae and Artemisium, rather than afterwards. In fact, this new evidence presents us with an entirely new way of looking at this period of history. If this sequence is true, the Athenians were planning for the decisive Battle of Salamis from the very beginning of Xerxes’ invasion. In this context, the significant battles that took place beforehand were simply designed to slow the Persians down, and the Greeks were one step ahead of the Persians all along.

So which version is closer to the truth? It’s fair to say the debate over this is quite convoluted, and there are issues with the evidence on both sides. However, let’s briefly (and I mean briefly) go over both arguments.

The biggest piece of evidence in favour of the Themistocles Decree’s interpretation is the famous prophecy the Athenians received from the Oracle at Delphi. In it, she recommends that they have faith in the ‘wooden walls’ of their ships and tells them the decisive battle will be fought at ‘divine Salamis.’ This seems to prove that the Athenians always planned for this outcome, and that the earlier battles were never designed to defeat the Persians. This is believable. Oracles were a crucial part of the ancient Greek world, and poleis often used these to help with decision making.

However, a prophecy is hardly definitive evidence, and the wording could have easily been altered after events to justify the actions of Themistocles and the Athenians. We also see Herodotus emphasise this oracle at length, so perhaps it was altered to better suit his narrative, which features fate as a key reason for historical events.

The main issue, though, is the fact that our stele was written in the early 3rd Century B.C.E, over two hundred years after the events it describes. Whilst later Athenian laws and decrees were inscribed and made visible to the public in this manner, this practice did not become commonplace until after the Persian Wars. This means the ‘original’ decree was likely written on a less durable medium like papyrus. How, then, more than two centuries after the evacuation of Athens and its later burning by the Persians, did whoever inscribed our stele get their hands on the original decree?

The answer is that they almost definitely couldn’t have, so it’s safe to say that the Decree of Themistocles is not a copy of an original proclamation. In all likelihood, it is a reimagining, likely cobbled together using oral tradition, inspiration from several other decrees and perhaps a dash of creative liberty. This doesn’t necessarily mean it is completely inaccurate, though. After all, the same factors that limit the decree also plague our written sources, most notably Herodotus, who also wrote his version long after the events themselves, and similarly relied on oral tradition.

Overall, I think neither version of this story can be considered objectively ‘correct’. Both have shortcomings, and it would be naïve to simply choose one as our only reliable source. History isn’t about finding one definitive timeline of events. Even today, it’s common for multiple versions of one story exist at the same time. It’s when looking at the Themistocles Decree with this in mind that we can see its true value.

We know that our decree was made in the early 200s B.C.E, and that it was found in Troezen. The keen-eyed reader may have noticed that both Herodotus’ account and the stele mention Troezen as one of the places the Athenian evacuees fled to. We also know that, much later on, Athens and Troezen remained on good terms, and fought together against the later threat of Macedonia. The threat to the Greek world posed by the Macedonians was significant, and likely brought up uncomfortable reminders of the Persian invasion from all those years ago. Perhaps, under this threat, the people of Troezen created this stele to commemorate their version of this crucial event. A way to remember a time when they stood with Athens to fight for their freedom.

The Themistocles Decree is an object that must have been deeply personal to the Troezenians, which I think makes its other name, the ‘Troezen Decree’, far more suitable. By reducing the discussion around this to simply challenging its reliability as a source, we strip it of its cultural value. This was a commemorative object; who are we to label it as a work of fiction?

Great Read👍

Love this Lou